The Dromcollogher Cinema Fire, September 5, 1926

The conversion of village halls into makeshift cinemas was a common practice in many rural villages in Ireland, right up to the 1940s. Prints were often borrowed from cinemas in larger towns or in Cork city, and then bicycled over to smaller venues (sometimes surreptitiously).

In the days before television and at a time when few had access to transport, travelling shows or one-off screenings provided an evening’s entertainment for small rural communities. Patrons usually got to see a feature and perhaps a couple of short films or some Pathé newsreels.

During the Free State period (1922-1937), the exhibition of films was still governed by legislation put in place by the UK government in 1909. The Cinematograph Act stipulated that cinema owners must apply for a licence to screen films, and that venues must observe strict safety standards (“An exhibition of pictures, by means of a cinematograph, or other similar apparatus, for the purposes of which inflammable films are used, shall not be given unless regulations made by the Secretary of State, for securing safety are complied with”).[1] Such standards included encasing projectors in fireproof booths, ensuring that the highly-unstable nitrate film–then the Industry standard–be properly stored and handled, and fitting out venues with several fire exits. The regulations were generally–though not entirely–observed by established cinemas but they were often ignored by operators of ad hoc venues/makeshift conversions.

Image Source: National Library of Ireland

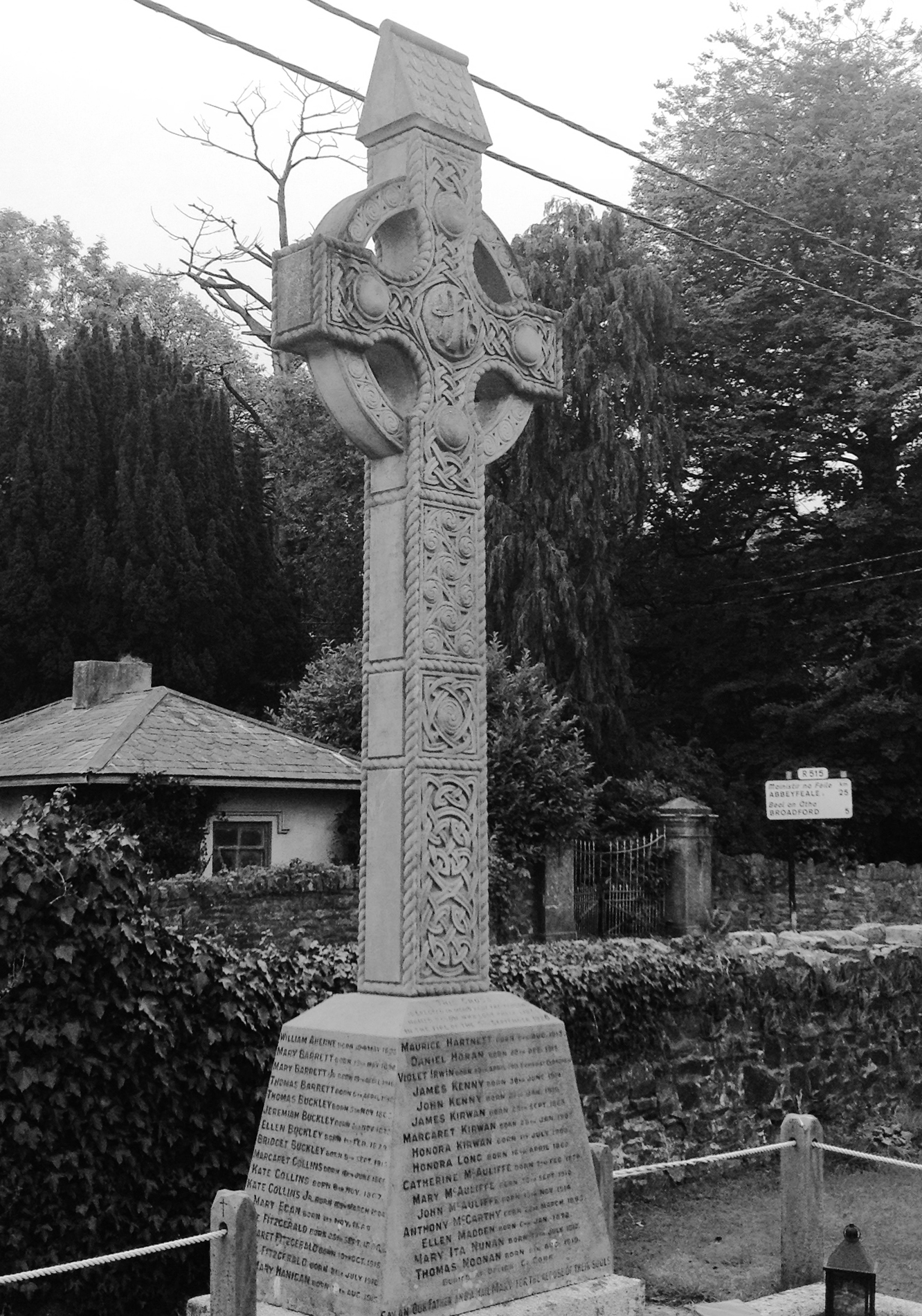

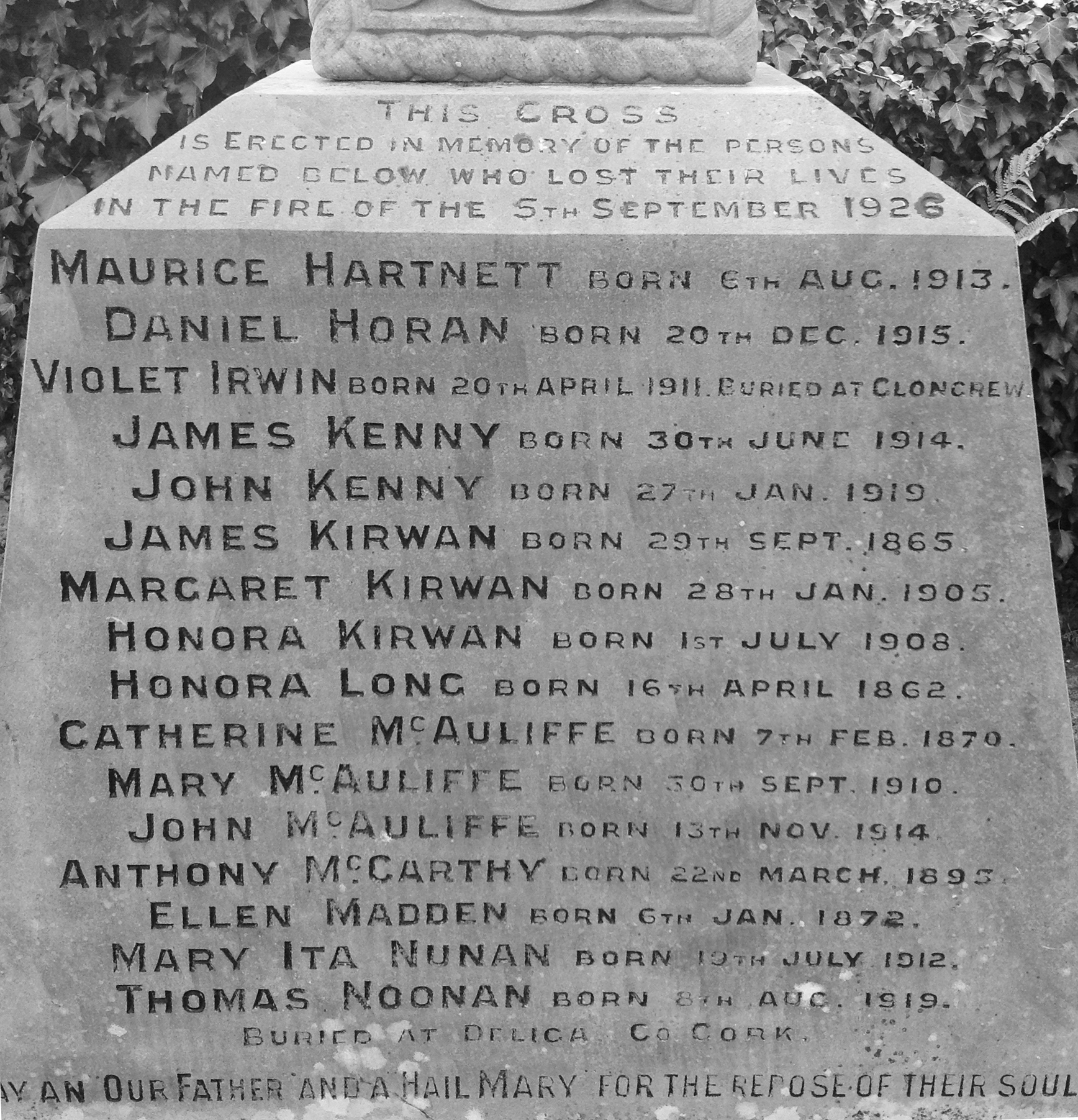

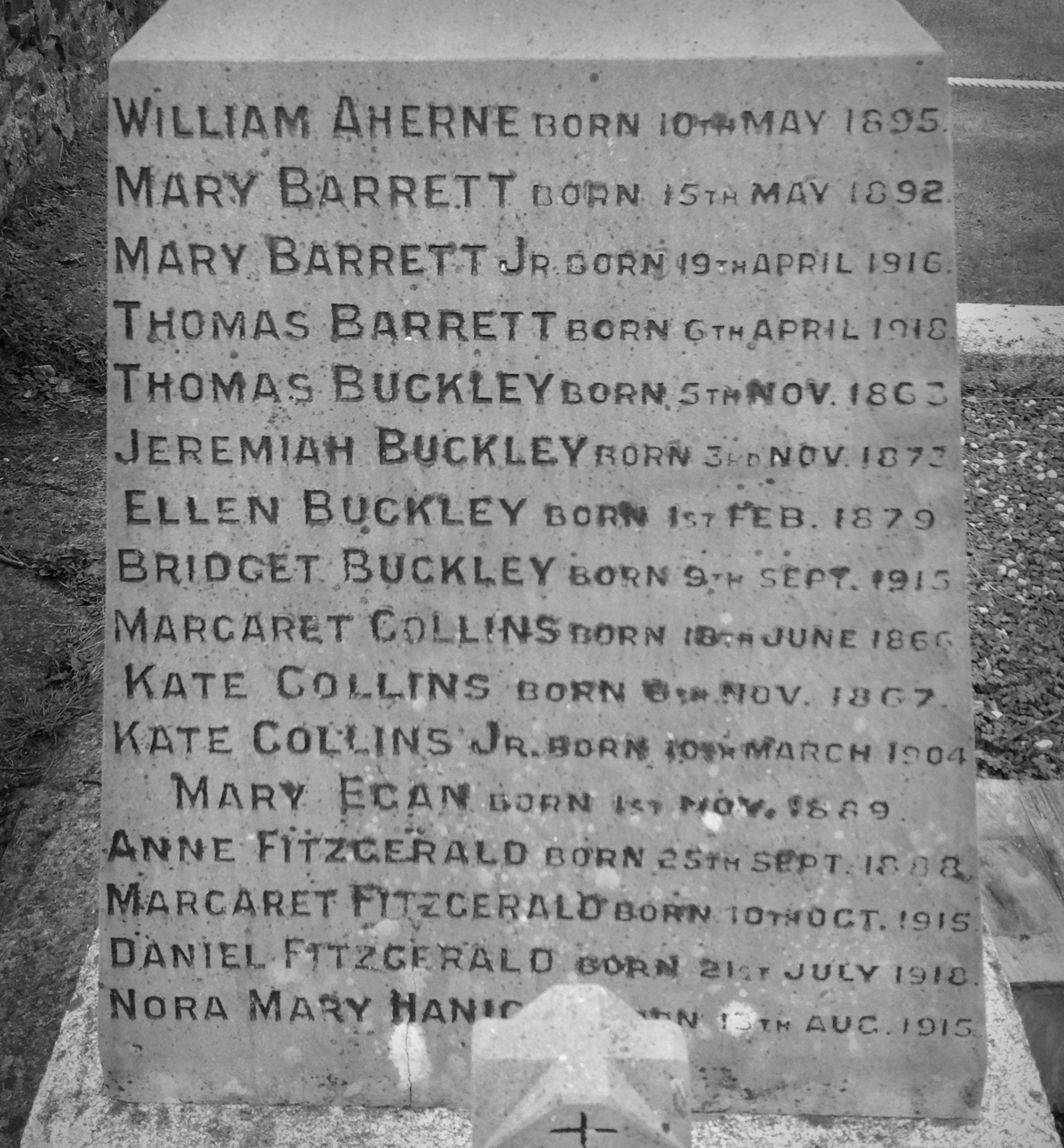

The consequences of such indifference to patron safety were tragically realized in the small town of Dromcollogher in West Limerick in 1926. Situated a few miles from the Cork border, its population was around 500 at the time, hardly enough to sustain a full-time cinema. However, local hackney driver William Forde identified a business opportunity that seemed too good to pass up. Through a contact, Mr. Patrick Downey (also reported as Downing), who worked as a projectionist in Cork city’s Assembly Rooms cinema, he arranged for a print of Cecil B. DeMille’s Biblical epic, The Ten Commandments to be bicycled over for an unofficial one-off screening. He rented the upstairs room of a venue on Church Street, later described by the Leinster Express as a wooden two-storey structure, and advertised his evening’s entertainment. He found a readymade audience among the churchgoers that milled out of the service in the adjacent Catholic Church and straight into the hall, many with their rosary beads still entwined in their hands. It was estimated that 150 people crowded into the room and ascended the ladder to the upstairs room. Though Forde had been informed by one local Garda that he could not run a screening unless the venue was equipped with fire blankets and exits, he and Downey disregarded the advice and, in a bid to reduce the weight for the cyclist bringing the reels from Cork, instructed that the fireproof metal cases be left behind in the city. A generator hooked up to a lorry was used to power the borrowed projector, and candles to illuminate the makeshift box-office. It was one of those candles, placed in close proximity to an exposed film reel, which sparked off a series of small fires that quickly developed into an inferno. Some of those seated closest to the main exit managed to escape, but those nearer the screen found themselves trapped and iron bars that had been placed on the few windows in the hall windows sealed their fate. Whole families were wiped out and the final toll came to 48 (initial estimates were higher, at 50). As newspapers of the time reported, 1/10th of the town’s population was lost.

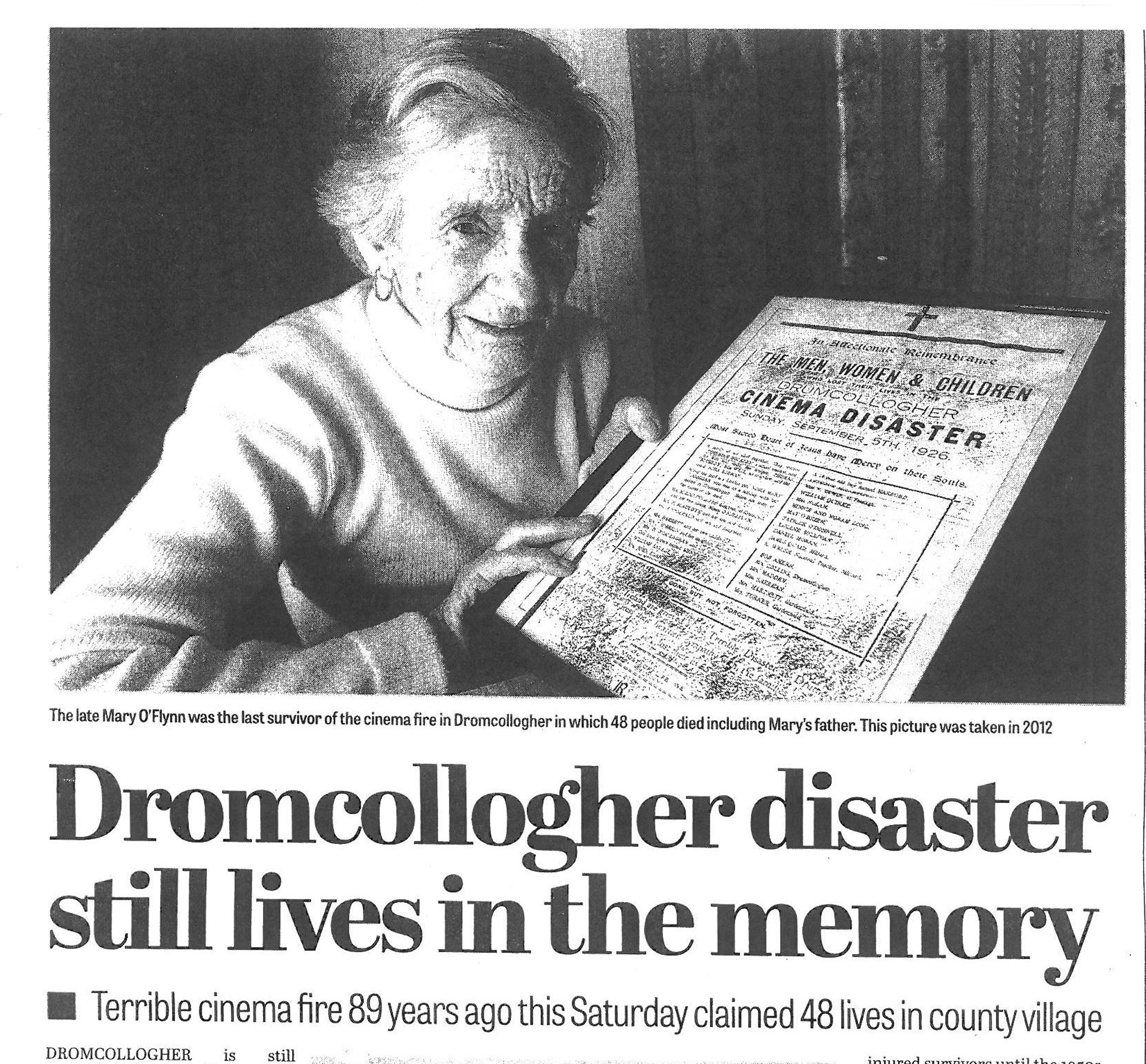

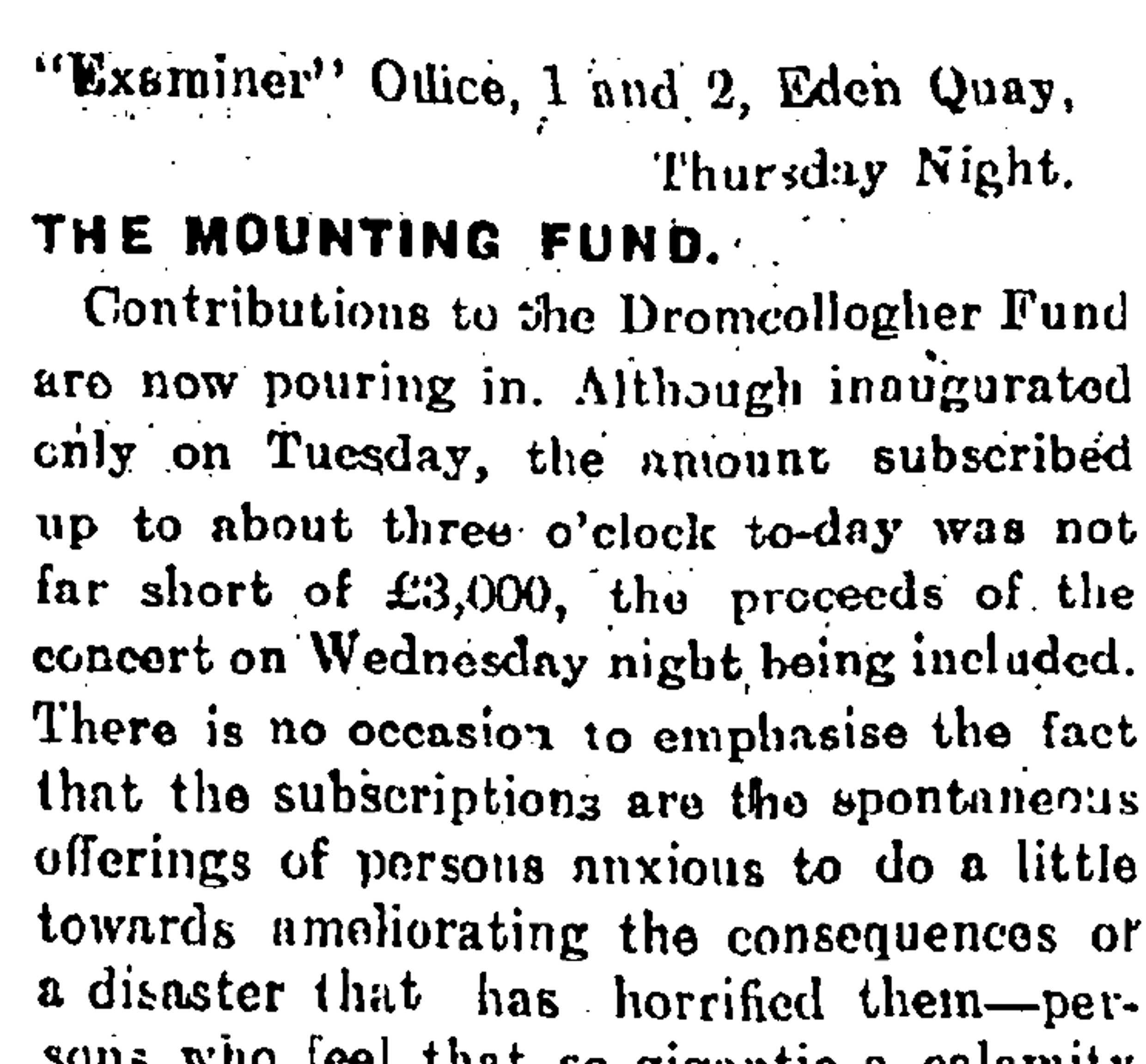

Newspapers around the world carried report of the Dromcollogher tragedy and a relief fund was set up for the survivors: Hollywood star Will Rogers was one of those that contributed. President William T. Cosgrave later travelled to the town to attend the mass funeral service held for the victims.

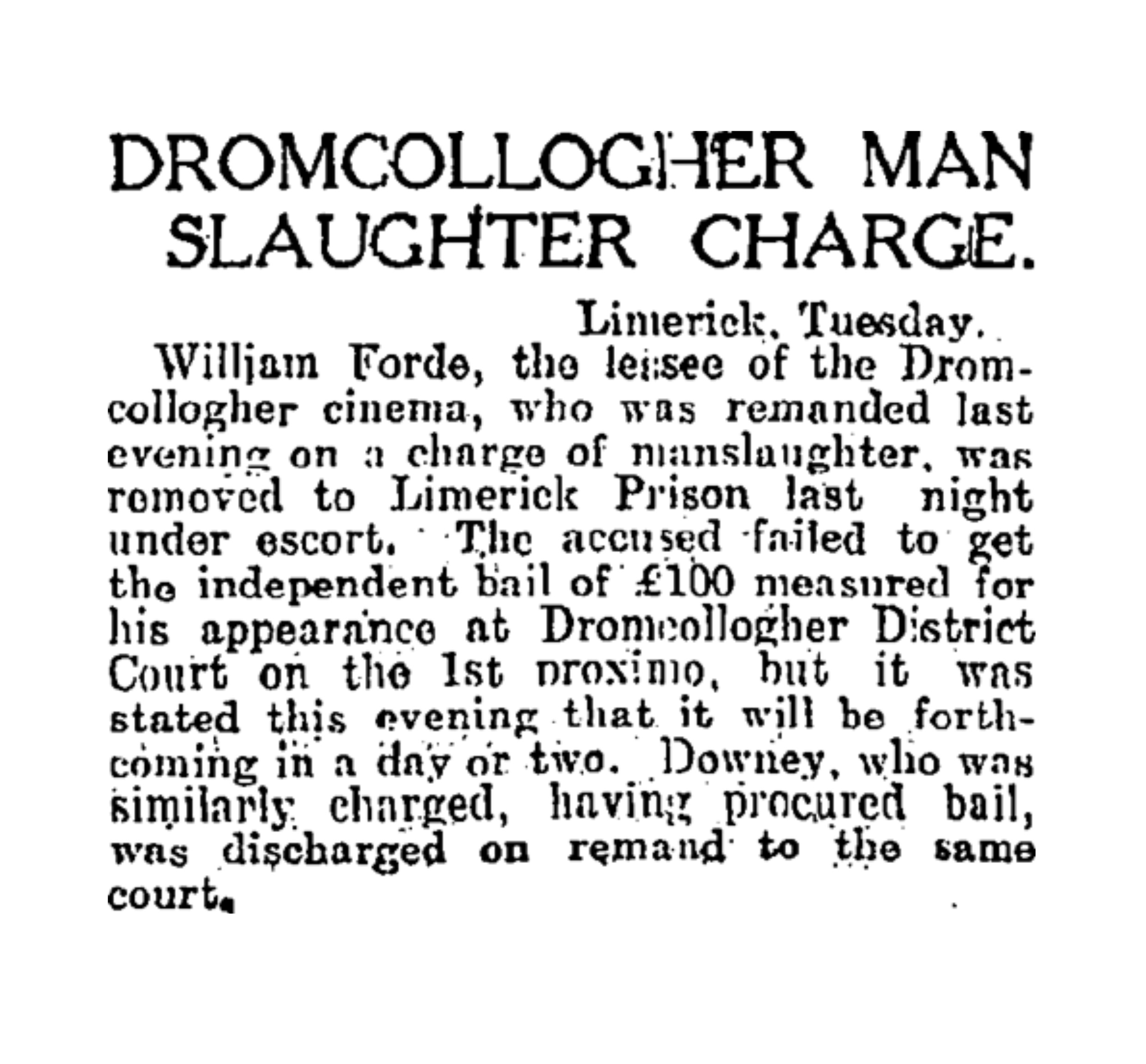

As for Forde and Downey, they were later charged with manslaughter but the State chose not to pursue the prosecutions. According to Barney Keating’s article (link below), Forde later immigrated to Australia and may have accidentally poisoned himself, and two others, while working as a cook in the Outback.

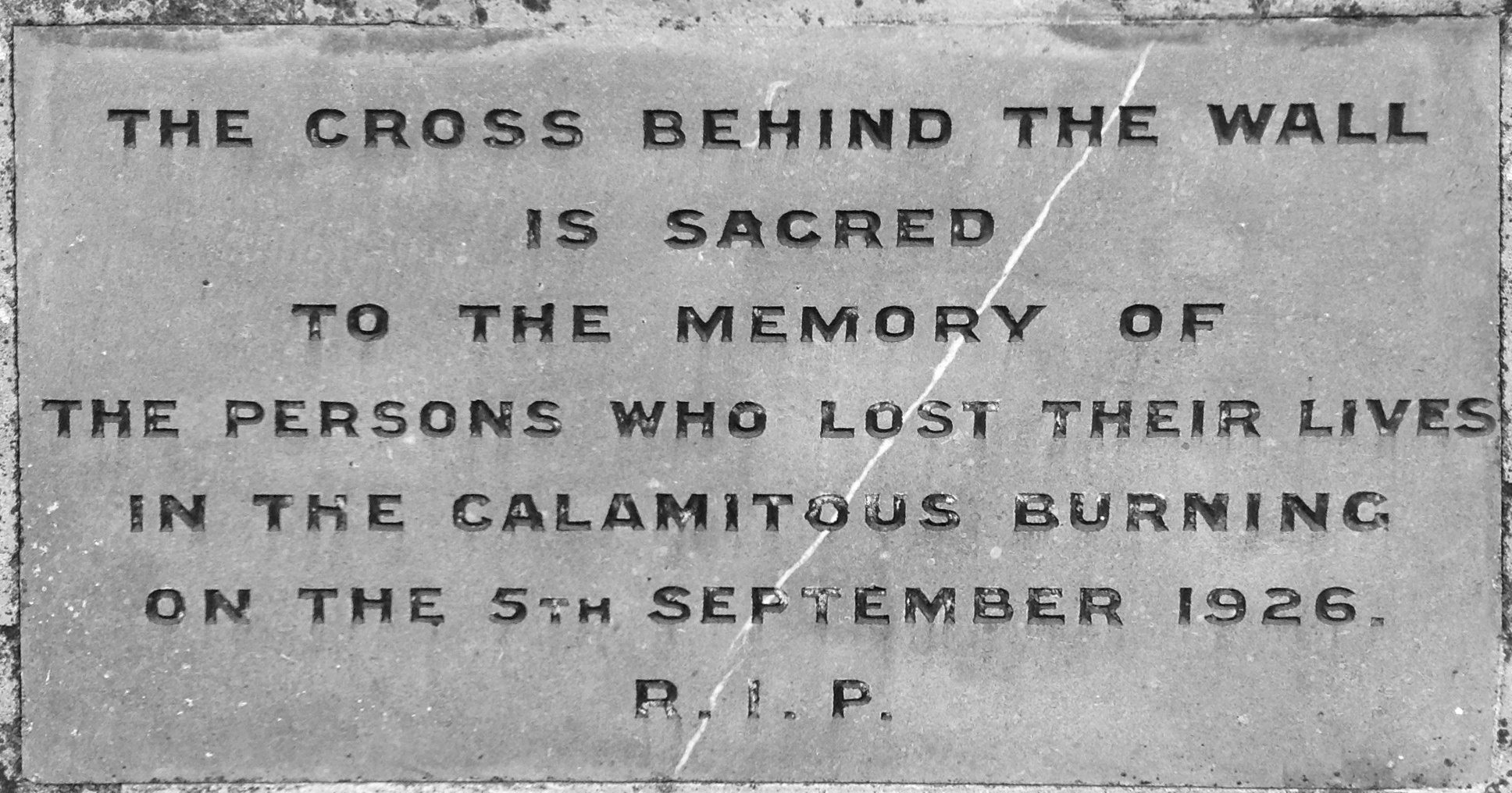

The “Dromcollogher Burning”, as it became known, holds the dubious honour of Ireland’s worst cinema fire. Sadly, it was not the last time safety regulations were disregarded in an entertainment venue: 75 years later the devastating Stardust Nightclub fire in Dublin also claimed the lives of 48 patrons.

[1]Cinematograph Act, 1909

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1909/30/pdfs/ukpga_19090030_en.pdf

Cork Movie Memories is grateful to Irish Newspapers Archives, Ireland’s Own, and The Southern Star, for permissions to reproduce the articles, below.

(click on the thumbnails to read the full article)

The Limerick City library website also hosts links to a number of press articles and research articles by Liam Irwin and by Barney Keating on the tragedy. See http://www.limerickcity.ie/Library/LocalStudies/LocalStudiesFiles/D/Dromcollogher/;

Readers may also find a recent article by Vincent Browne, published in The Irish Times on Sept. 2006, of interest: https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/1926-fire-tragedy-recalled-1.1002102